The Writer’s Dilemma

It was with my brain beating on the backs of my eyes, my shirt on backwards, hungover out of my mind, that a set of data confirming something I’d long suspected was presented to me—a man in a v-neck sweater motions to a graph: well yes, writers as a profession are at a disproportionate risk for alcohol abuse, and on a more serious level, at risk for suicidal behavior.

My first exposure to alcoholics as a subset of the population was not with creatives, but with farmers. I grew up in a tiny corner of the world, teeming with wild ducks and dead trees, the harvest permitting boys to leave school early to help on the family farm. Iowa is the largest exporter of corn to the rest of the United States, used primarily for ethanol, but we also love our corn beer—Busch lite cans littering the student section after every football game. Most people I knew had at least one alcoholic parent. It didn’t tear families apart in the pop-culture metropolitan sense, because there was nowhere for anyone to go.

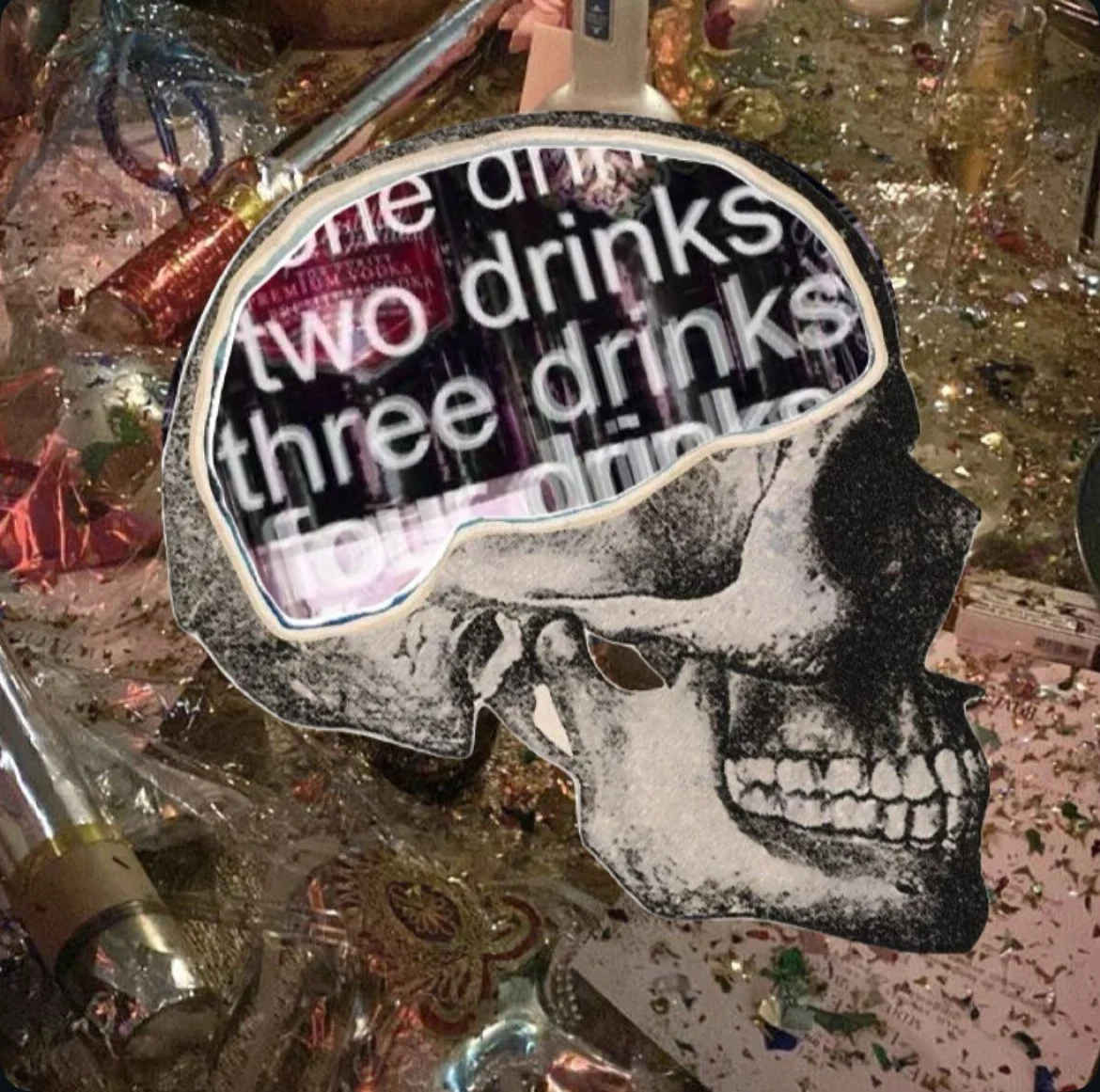

I’ve been writing since I could read, and most of it was garbage up until a few years ago. I can logically tie this into the mere development of the craft, over long hours of toiling—and not to discount the years of learning, but it’s no coincidence that a few years ago is when I also started drinking regularly. And not a glass of wine every week or so. I am nothing if never timid. It’s no secret that people have been drinking since forever: The 20s in Paris, the 60s in rural America and Los Angeles, these creative revolutions happened in circles where substances were rampant and destructive. New data sets confirm that Gen Z isn’t drinking less than millennials or Gen X, it’s just that we came of age in an economic crisis. It’s obvious we would be drinking less at bars and restaurants, and generally we were too young to be properly accounted for in consumer surveys until recently. The continuing cycle makes me feel connected in a way to my forefathers, the contributors to the Western literary and poetic canons. Every time my creativity is bolstered by it, it's like I’m possessed by Ginsberg or Yeats. It’s the torch we pick up without even noticing.

I don’t drink intentionally for the purpose of it contributing to my creative process. However, it does, incidentally, almost every time, as is the case with many other things too—half of my titles, finishing lines, and opening paragraphs have come to me in divine revelation directly from the bottle’s neck. It would be stupid to argue that people I’m connected with in creative fields drink in a calculated way, where it’s used specifically as a tool. We drink because we can, because it’s there, because it makes us unafraid to say what we really mean. This is the struggle of the writer that continues outside of time: telling the truth, uninhibited. I’ve said many times that to be a good writer is to be a good liar. Growing older I’m less certain this is the case.

Here we get to the real meat of the chicken and egg debacle: do writers drink because as sensitive people with an inclination for tapping into uncomfortable feelings, we simply cannot handle the things we tend to find out—or, out of those predisposed to addiction, is writing is just the artistic way of coping? The shoe doesn’t fit everyone, and not everyone who drinks writes, but almost everyone who writes for a paycheck… well.

Writing that isn’t journalistic, academic, or otherwise purely fact-based is difficult to do, and even more difficult to do regularly for the emotional toll it takes. You’re constantly reliving bad things that have happened to you for your art, so you drink to make it more quiet for a few hours. Because you drink so much, bad things continue to happen, so you have more to write about. Eventually you get into this strange backwards net where you can’t write without it. Sometimes true, sometimes not. My experience is that you simply cannot make gritty, uncomfortable, dark, etc ideas come alive if you’re not in a gritty uncomfortable place yourself. Maybe to be a writer is to live permanently in your head, and for many people generally it can be a straining place to be. Maybe torturing yourself is just part of the job. The chicken and egg continues. I’m just one out of a long line, obviously I was never going to be the one to figure it out.

William Burroughs has authored some of the most disgusting, visually graphic, disturbing prose about addiction I’ve ever read. But it’s important, and it’s beautiful. And it certainly wouldn’t have happened if he hadn’t been shooting black tar heroin in his prime, and taking opioids right up until he died. Hemingway was a piece of shit who drank himself to suicide, but With Hills like White Elephants remains one of the most widely taught short stories in American high schools. Donna Tartt and Bret Easton Ellis did loads of coke, together, in rural Vermont, and you can almost feel the wired jaw clacking through the pages. I do not want to make the dangerous argument that good writing can only come from addiction. I instead want to make the claim that maybe art is the product of pain, and some of the worst situations people can go through are brought upon them by themselves, through exploitation of their dopamine centers.

The nature of cyclical reasoning and questions, i.e. chickens and eggs, necessitates that they are unanswerable. Coming up with some brazen statement about why prolific household names struggle and toil with substances, as someone who is neither a psychologist nor a prolific household name, would be futile and tactless. However, the fact that we don’t have a concrete answer doesn’t make this topic less pertinent. As someone who’s pipe dream is to have a body of work that I’m proud of at the end of my life, as someone who wants to publish manuscripts and give something great back to the big wide world, the reality of the writer’s dilemma is something I need to reckon with personally. Today, I’m writing this at 14:39 at a bar I used to live above with a half pint of Guinness making a wet ring on my to do list. Maybe few are chosen and even fewer make it out alive.