In the Neon Plastic Cosmos

Yesterday, I was playing in the sandbox with my little brother.

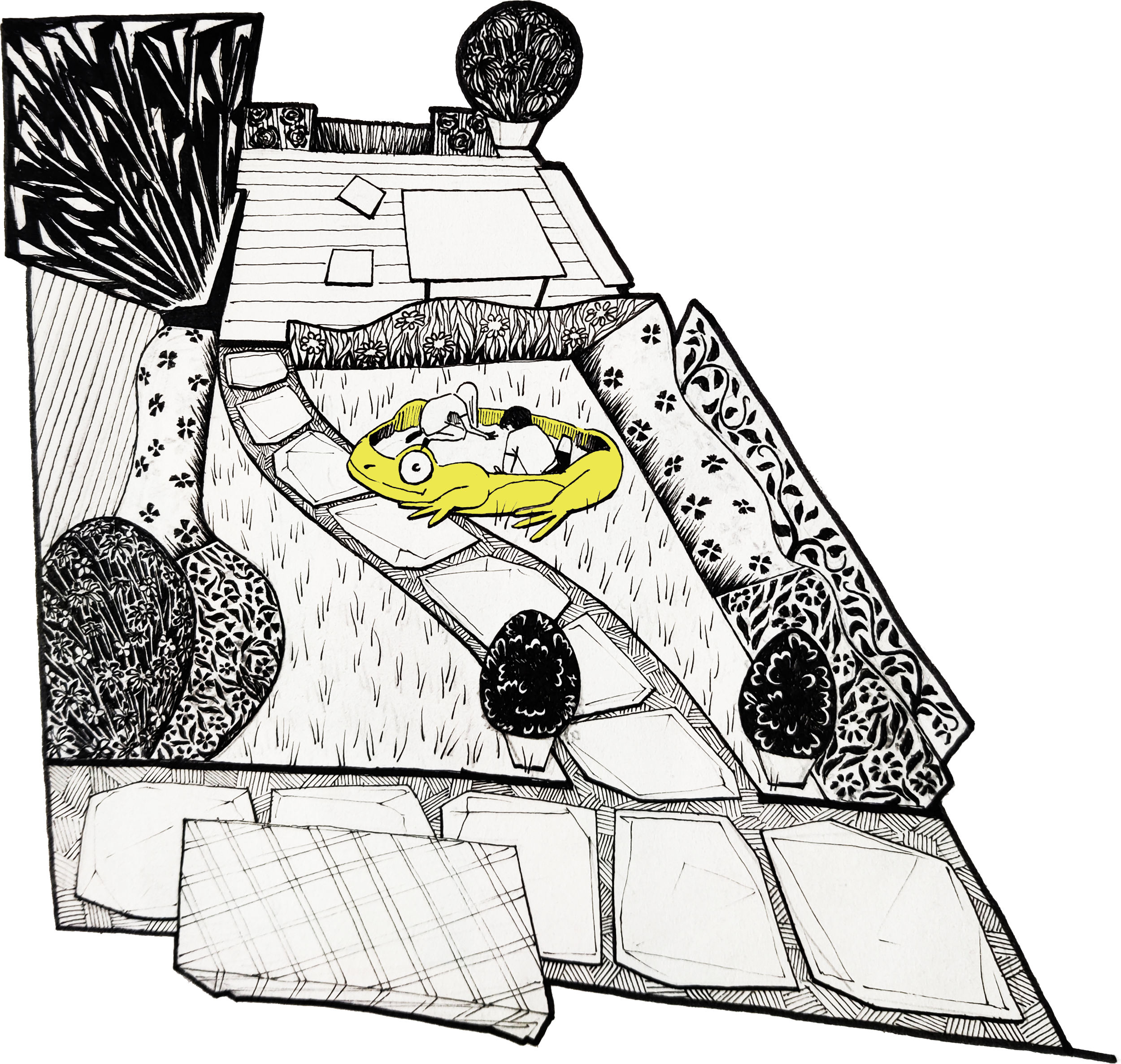

It was a hideous neon-yellow frog-shaped monstrosity — in this case, the sandbox, not my brother — that, with its shining cheap plastic, almost ironically contrasted with the pompous garden of my parents. A garden full of plants, full of flowers, an oasis of overwhelming green when you stepped over the threshold of the back door. Overwhelming but not oppressive, a wilderness caught between the lines. So precisely tracked that, when you looked closely, it seemed to stop abruptly before the margins of the paving stones that ran in winding paths through the garden. An illusion of overgrowth in which the presence of every flower, the location of every plant, had been thought through. The awkwardness of that yellow plastic amidst my mother’s miniature oasis seemed almost a metaphor for the presence my little brother and I held in those first years. A visualisation of the place we had occupied, a stain of evidence, a crack in the perfect control she tried to exude. The awkwardness of a compromise that did not mediate but squeezed two worlds together. A neon-yellow frog among my mother’s hydrangeas.

When I think back to that time, I don’t know if the images that appear behind my eyelids

are mere crafted stories around photographs or real memories. Whether the words resounding in the fragments are spoken by real voices or are hollow echoes. In any case, I know that the feeling of being young with which those memories assail me — a feeling of carefreeness that I could best describe as floating, the same feeling I imagine astronauts experience the first time they glide weightlessly through space — is a feeling I made up. A feeling later attributed to the picture of being a child. At that time, being a child would mean nothing to me yet — a feeling without value, as values are only constructed through comparison of what they are not. How can you be floating when you haven’t felt the pressure of the wind when you fall down? And even if I did feel my hands drift through the sky at times, I doubt it felt as light as I imagine it does now.

Still, from time to time, I lock the fragile cage of my own deceit and float above the sand

within that yellow monstrosity. Weightless, a feeling illuminated by its antagonist, a memory of floating visible by the plunge when my swim bands were first slashed off.

Throughout the summer of 2007, my brother and I spent all of our time cross-legged in the sultry sand of the yellow frog. It was the type of hyperfixation that, without a doubt, all of us have experienced in some form or another during our childhood years — an obsession that seems to be defined by the characteristics of its authors. Drawn on youthful capriciousness, these short-lived, intense flames of passion burn so profoundly that they seem an unmistakable part of daily life. Rather a habit than a hobby, as the possibility of getting bored with it ceases to exist. A Barbie doll, Hot Wheels, or nowadays iPad games and YouTube — these toys suddenly seem to be the only things worthy of attention. A temporary tunnel vision, and during those sun-soaked months in 2007, it was only the yellow frog my brother and I saw down at the end of the dimmed passageway.

Day in and day out, we were building forts and castles, preparing sand pastries, and digging holes into the earth’s crust. From the moment we rushed downstairs and hastily devoured our breakfast until it was time for dinner and our sandy paws were no longer welcomed inside, we would sit there, fenced between the walls of our two-square-metre desert world.

During those months, my brother and I initiated a range of different projects within that dusty pool of sand. The grains that lay within no longer functioned as a playground but transformed into a construction site, which we navigated with the gravity one might expect from professionals on the job. We launched dozens of projects, though each born from vigorous brainstorming and fueled by our boundless enthusiasm, only a few seemed to withstand the dulling of time. What initially had been an arbitrary purchase — a bargain our mother had accidentally stumbled upon while strolling through the local dollar store, a capitalist’s wet dream that looked as if an AliExpress warehouse had just vomited all over the place, with every shelf sagging under brightly colored, poor-quality trinkets and the sour-sweet breath of cheap plastic and single-use fossil fuels penetrating between the aisles — the frog quickly promoted from prop to the centerpiece of our summer stage.

Somewhere near the end of our school vacation — although I couldn’t tell you which month, since as a kid, summer has that tendency to blur the days into a monotone routine — we found ourselves in the midst of our latest enterprise, and the frog once more converted into a worksite.

This project was one of our simpler ones — or at least in theory it was, since its execution only required one single (and most elemental) movement: shoveling. It had already been in the scaffolds for almost a week by then, which by our standards already marked it as exceptional, thus making it a rare contender with a real chance of survival. Named with the creativity only the combined imagination of a five- and seven-year-old could spawn, we christened it “Operation Tunnel to China,” or OTC, as we preferred to call it, sensing that the abbreviation lent it a kind of military gravitas that did justice to its vision. Where the idea had first come from — television, a classmate, a bedtime story — I no longer recall. In the end, it doesn’t seem to matter, as it can’t explain our stubborn determination to finish the project. What mattered was not the origin but the audience: our mother. When we told her about our newest plan and proudly showed her the growing piles of displaced sand, she only smiled and wished us luck, her voice dipping into that peculiar adult condescension, echoing her amusement at our childish naïveté, an undertone leering in the curled-up corners of her smirk.

That smirk was enough. We became resolute, convinced that together there was nothing we could not build. We approached the task with a seriousness that could only be explained by the stubbornness gene we both seem to carry, woven in our shared DNA — and perhaps also by the fact that Phineas and Ferb had been looping endlessly on television that summer, giving birth to an entire generation of delusional anklebiters who believed they could, in fact, locate Frankenstein’s brain, find a dodo bird, paint a continent (and drive their sister insane). Still, even we knew that such an undertaking required expertise, and although my brother and I counted a good twelve years of combined life experience, we decided that morning to enlist the boy next door to partake in our quest.

About this little boy, there is only so much I can tell you.

When I dig through my mind, scraping and sifting through memories scattered like grains, only a faceless image remains. Even the word image feels wrong — nothing visual appears. No picture surfaces in my thoughts, only a cluster of invisible memories: traces of sensations, textures of the past without a frame to hold them. It’s not an image that reminds me of how tall he was, but the feeling that he towered above me. I don’t recall that he had braces, but I hear the whisper of his lisp slipping softly through the air. His laugh? Not the sound — only the irritation it left behind, a hum that never faded. Strange, isn’t it, how memory works? How it tucks away the useless details and guards them like relics — information we never chose to keep, yet still carry with us; fragments of the past tense spelled out in the now. For nine years, I saw him almost every day. Seventeen years later, I can still feel him beside me in the sandbox, still hear the echo of his voice, still recall what he said that day. But his name? Gone. Apparently, my mind didn’t think it was worth saving.

No, about this little boy, there isn’t much I can tell you.

Only that the trampoline in his garden was way cooler —

but maybe that’s all that needs to be remembered.

So I sat there that afternoon, kneeling in the corner of our neon-yellow domain, toiling underneath the scorching sun, digging not a hole, but a promise — buried deep underneath the desert of a thousand grains.

If I close my eyes, I can still feel the sand scrape against my skin, as a thousand tiny drops of emery paper, dripping down from the brittle heap pulverized inside my fists. Wiggling their way into the wrinkled skin and slipping into the creases between my fingers, as a calm stream meanders down along the curves of my hands as though they were small rivers carving out new terrain.

My mother had been sitting only meters away, reclined in a lounge chair on the porch. Beside her was the boy’s stepmother, and after a while of discussing the latest developments of our current enterprise — with what I can only describe as a kind of belittling affection — they seemed to drift into a conversation that carried their attention elsewhere, away from us and the yellow frog. But had my mother’s eyes coincidentally wandered away from the frowning face of the woman sitting next to her, she probably would have thought I was having a stroke, seeing me gawking for a good ten minutes over a sand stream that I refilled and refilled and refilled until my nails were black and my hands felt bruised — a sensation, I found out, that got more and more fascinating the longer I seemed to focus on it. The more I repeated the motion, the more mesmerizing it became; the repetition became a spell of its own — as for a kid, the intangibility makes you feel powerful, the uncountability of those tiny grains, so many separate objects held in the palms of your hands, all at once.

There was someone, however, who did notice my hypnotic state, and before the fourth sand stream that flooded from my fist had dried up, the shrill voice of the boy echoed pedantically through the garden. “Did you know that there are as many stars and planets in the universe as grains of sand on the Earth?” The boy looked at me with what I can only describe as the gaze of a true snotaap — “snot-nosed kid” comes close. A gaze that, even to this day, can ignite a peculiar, burning rage inside me — a sudden flare of pure aversion. His eyes were narrowed, as if he was actively trying to poke me with his stare — the visual equivalent of eighth graders yelling “What are you gonna do about it, huh?” to each other across the schoolyard. And that smirk, plastered across his face, seemed the very embodiment of an eye-roll, silently laughing as I stumbled over words before they’d even left my mouth, tripping over syllables that hadn’t yet made their journey converging into sound. As my startled look and lack of audible response gave away that, in fact, I did not know that, his eyes started to gleam with that condescending sparkle of a know-it-all who’d discovered that they held a card no one else could play. These kinds of snarky, prying comments were nothing out of the ordinary, as the boy was a few years older than me — something he would never let me forget. His stories of fugitives in the neighborhood or spies in the schoolyard had once held me spellbound, though by then I had grown tired of his tales. Nowadays, I had stopped paying much attention to his braggy shows of sturdiness, mostly because I found them more annoying than cool. Secondly, because I had started to notice the frowns of disapproval that crept into my parents’ faces, or the self-righteous disdain that seeped through the creaks of their quiet conversations after I repeated some of the stories he told me at times. So when he uttered his latest wiseacre remark, I automatically looked up to search for that disavowment in my mother’s squint, the eye-roll in her posture, or the invisible shaking of her head. When I met her gaze, however, I didn’t find the reassurance that it was indeed another lie, nor the slightest trace of disapproval — only a mere nod, an almost imperceptible acknowledgment that indeed, this time, he was right. In the background, the boy’s voice rose again — shrill and squeaky with excitement — like a car finally taking off after revving impatiently at a red light. But I barely heard the words rumble through the sky; his story had roared ahead, and I was left stranded in the fumes behind.

I wish I could verbalise the thoughts that were bouncing against the corners of my skull at that moment. I wish I could articulate the poetry of that epiphany — the first grasp of the realization of what it meant to be alive — that little me felt slipping through my fingers all those years ago. But every time I sit down, hunched over my laptop, my fingers suddenly seem to be lost for words between the letters on the keyboard. For a couple of weeks now, I have found myself stranded at the side of the road, standing next to a green hectometer sign, stuck at the same exact location in the storyline that I can’t seem to get past.

I don’t remember a lot of my childhood years. From time to time, when I’m sipping wine and spooning up memories with old friends, or leafing through one of the photobooks of my early years, I take my shovel and step inside the sandbox of my mind, and try to sweep through the sand of my unconsciousness. A process of excavation from which I more often return empty-handed, unable to hold the grains that slip through the creeks of my grasp. A part of the reason I fail to do so is the pressure I tie myself to — the mission to remember. However, most stems from the anxiety, the uncertainty of whether a memory is real or crafted — an altered truth that was replaced in my thought palace all those years ago. When I was younger, I invented a ritual for those memories I didn’t want to carry into the next day — a file system, conveniently ignoring their existence away, like the junk drawer in your kitchen, stuffed with those blue envelopes, banned from reality and postponed from payment today. I would close my eyes and imagine I was walking through my mind, my thought palace, down the spiral staircase to the basement — dusty ladder, flickering bulb, and all — and lock the to-be-forgotten memory in one of the rusty boxes safely away.

Now my feet are wet, my socks are soggy, as the basement collapsed beneath what was hidden but not forgotten.

As I walk through my palace, the water surface wrinkles and ripples beneath my shoes — I see a mirror of flooded thoughts.

Around me, the books are floating, drenched in the stream carrying the shore of the past,

their words now faded, too soaked with that which remained, to tell me what was —

which letters were written, which words erased, which sentences added or thoughts replaced.

So let me now follow the track through the flood’s embrace,

where the ink bled out I turn to this new page, a blueprint of the memory traced.

It would be foolish of me to pretend, to write and present to you as if I still knew what exactly went through my mind that moment when I was sitting there, cross-legged in the sultry sand. Of course, this is fiction, and the beauty of fiction is that it is not solely the truth — that it is a glorified version: the experiences, the feelings, and observations we make in the greyness of daily life, an empty coloring book filled in with the pencils from our etuis. The art of swiping the yellow marker over the black outlines of the sandbox printed on the pages, to color meaning into what often seems blank. Still, this memory is one of the few that I can see floating safely on top of a side table, bobbing through my thought palace. Even though when I reach out to grab it, the letters seem blurred and sprung, I can still feel the memory when my finger brushes against the page. It carries a tangibility that can’t be expressed by the words printed on the page — a truth that seems so fundamental to me that I can’t write it, transform it into fiction. No, I can only explain it with the traces of feeling its meaning left in the ruins of my brain.

And so I sat there that afternoon, kneeling in the corner of our neon-yellow domain,

toiling underneath the scorching sun, digging not a hole, but the emptiness that remains —

buried deep underneath all answers, the question is a desert of a thousand grains.

As the last layer of water, circling in a draining bath, the dusty pool in my hand seemed eager to dry up fast.

As if the sand recklessly tried to escape those mere seconds in which they were less — solely grains, separated from the rest.

Not in the heap between my hands nor absorbed by the growing pile between my legs.

Suddenly, the stream was no longer floating but diving headfirst towards the embrace of anonymity in the depths.

How frightening it must be to fall.

Suddenly ripped away from the safety of your hiding place, no longer invisible within the totality of it all.

How alone it must feel to disappear into the masses, becoming nothing again when you drown.

In my pockets, I felt the sand; its weight was dragging me down.

I was no longer floating, but headed for the ground.

Yesterday I was playing in the sandbox with my little brother.

Now I’m smoking my last cigarette before bed.

While I look up to the sand grains scattered across the night sky, I wonder

about all the answers I will never get.

Am I living inside the sandbox — is the yellow monstrosity our universe, containing the totality of it all?

Or is it all inside my head, as a foolish man once said, that I know that I know nothing but only to stand tall?

Here, in this neon plastic cosmos, I sit small.

With my thoughts buried in our tunnel to China, as an ostrich, I am comforted by the solitude of denial,

because when you don’t see what is approaching,

you don’t fear what is out there at all.

Longing for meaning, trapped in a world where only ephemerality seems to consist,

yesterday I was playing in the sandbox with my little brother.

Today I suddenly seem to exist.